"We often forget that the American pattern of suburban development is an experiment, one that has never been tried anywhere before. We assume it is the natural order because it is what we see all around us. But our own history — let alone a tour of other parts of the world — reveals a different reality. Across cultures, over thousands of years, people have traditionally built places scaled to the individual. It is only the last two generations that we have scaled places to the automobile.

How is our experiment working?

At Strong Towns, the nonprofit, nonpartisan organization I cofounded in 2009, we are most interested in understanding the intersection between local finance and land use. How does the design of our places impact their financial success or failure?

What we have found is that the underlying financing mechanisms of the suburban era — our post-World War II pattern of development — operates like a classic Ponzi scheme, with ever-increasing rates of growth necessary to sustain long-term liabilities.

"Civil Engineer Charles Marohn worked his whole life trying to make his community better—until the day he realized he was ruining it.

Marohn primarily takes issue with the financial structure of the suburbs. The amount of tax revenue their low-density setup generates, he says, doesn’t come close to paying for the cost of maintaining the vast and costly infrastructure systems, so the only way to keep the machine going is to keep adding and growing. “The public yield from the suburban development pattern is ridiculously low,” he says. One of the most popular articles on the Strong Towns Web site is a five-part series Marohn wrote likening American suburban development to a giant Ponzi scheme.

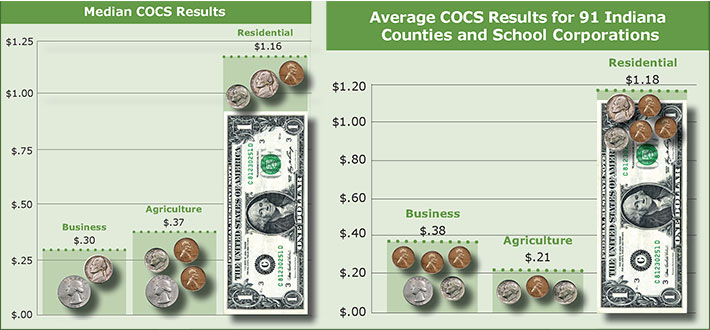

Here’s what he means. The way suburban development usually works is that a town lays the pipes, plumbing, and infrastructure for housing development—often getting big loans from the government to do so—and soon after a developer appears and offers to build homes on it. Developers usually fund most of the cost of the infrastructure because they make their money back from the sale of the homes. The short-term cost to the city or town, therefore, is very low: it gets a cash infusion from whichever entity fronted the costs, and the city gets to keep all the revenue from property taxes. The thinking is that either taxes will cover the maintenance costs, or the city will keep growing and generate enough future cash flow to cover the obligations. But the tax revenue at low suburban densities isn’t nearly enough to pay the bills; in Marohn’s estimation, property taxes at suburban densities bring in anywhere from 4 cents to 65 cents for every dollar of liability. Most suburban municipalities, he says, are therefore unable to pay the maintenance costs of their infrastructure, let alone replace things when they inevitably wear out after twenty to twenty-five years. The only way to survive is to keep growing or take on more debt, or both."

- Leigh Gallagher, Assistant Managing Editor of Fortune, writing in Time MagazIne,

The entire article, "The Suburbs Will Die: One Man’s Fight to Fix the American Dream," is here.

Cost of public services provided: water, sewer, roads, schools, fire, police,

medical rescue, etc., per dollar of tax revenue raised for each land use/zoning

Cost of Community Services (COCS) studies are snapshots in time of costs versus revenues for each type of land use. They provide a baseline of current information to help local officials and citizens make informed land use and policy decisions. In every study conducted during the past 20 years, farmland has generated a fiscal surplus to help offset the shortfall created by residential demand for public services.

These studies show that, nationwide, residential development is a net fiscal loss for communities. Taxes on farmland, forest, open land, and industry generate more in tax revenue than they cost in services, while taxes on residential development fail to cover costs.

In other words, replacing farmland with residential development drives your taxes up.

The developers and a few businesses get richer. You get stuck with the bills.

Northfield Township Manager Steve Aynes confirming this in a 5/30/2017 interview. ( Watch the original Video )

Read the 2016 American Farmland Trust Cost Of Community Services Study

Read the 2010 AFT Costs of Community Services Study - viewable as an online slideshow

Read the 2010 AFT synopsis of the Costs of Community Services Study - viewable as an online slideshow

404:

http://www.communitypreservation.org/community_services.pdf

"When a government body provides a subsidy to a developer, it must finance that payout, usually through debt. Governments typically rely on three different methods to repay this debt - bonds, TIFs or STAs.

Local governments use TIFs to subsidize developers in order avoid statutory requirements that require voters to evaluate and approve the debt via referendum.

TIFs mean that property owners outside the development pay both the cost of public services to themselves

AND a portion of the cost of providing services to the new property owners covered by the TIF. In other words, current residents carry more than their fair share of the tax burden for public services." (source: http://www.controlgrowth.org)